Insertion into the Austrian orbit

Having become a free municipality, Trieste had to face new and more powerful pressures, both of a military and economic nature, from Venice, which aspired to assume a hegemonic position in the Adriatic. The disproportion in demographic, financial and military terms between the two cities foreshadowed a future inclusion in the Venetian orbit for Trieste with the consequent loss of its independence as had already happened previously for many Istrian and Dalmatian centers. In 1382, yet another dispute with the Serenissima - which had led, after an 11-month siege, to the Venetian occupation of Trieste from November 1369 to June 1380 - led the city to place itself under the protection of the Duke of Austria who committed himself to respect and protect the integrity and civic freedoms of Trieste (the latter were largely downsized starting from the second half of the 18th century).

Creation of the free port and development of the city

In 1719 Charles VI of Austria created a free port in Trieste whose privileges were extended, during the reign of his successor, first to the Chamber District (1747), then to the whole city (1769). After the death of the emperor (in 1740) the young Maria Theresa of Austria ascended the throne who, thanks to a careful economic policy, allowed the city to become one of the main European ports and the maximum of the Empire. In the Teresian age the Austrian government invested substantial capital in the expansion and strengthening of the airport. Between 1758 and 1769, works were prepared to defend the pier and a fort was erected. In the immediate vicinity of the port were built the Stock Exchange (inside the Town Hall, around 1755), the Palazzo della Luogotenenza (1764), as well as a department store and the first shipyard in Trieste, known as the squero di San Nicolò. In those years an entire district began to be built, which still bears the name of the empress (Borgo Teresiano), to accommodate a population that was growing in the city and that at the end of the century would have reached about 30,000 inhabitants, six times higher than that present a hundred years earlier. The remarkable demographic development of the city was due, in large part, to the arrival of numerous immigrants coming mostly from the Adriatic basin (Istrian, Venetian, Dalmatian, Friulian, Slovenian) and, to a lesser extent, from continental Europe (Austrians, Hungarians) and Balkan (Serbs, Greeks, etc.).

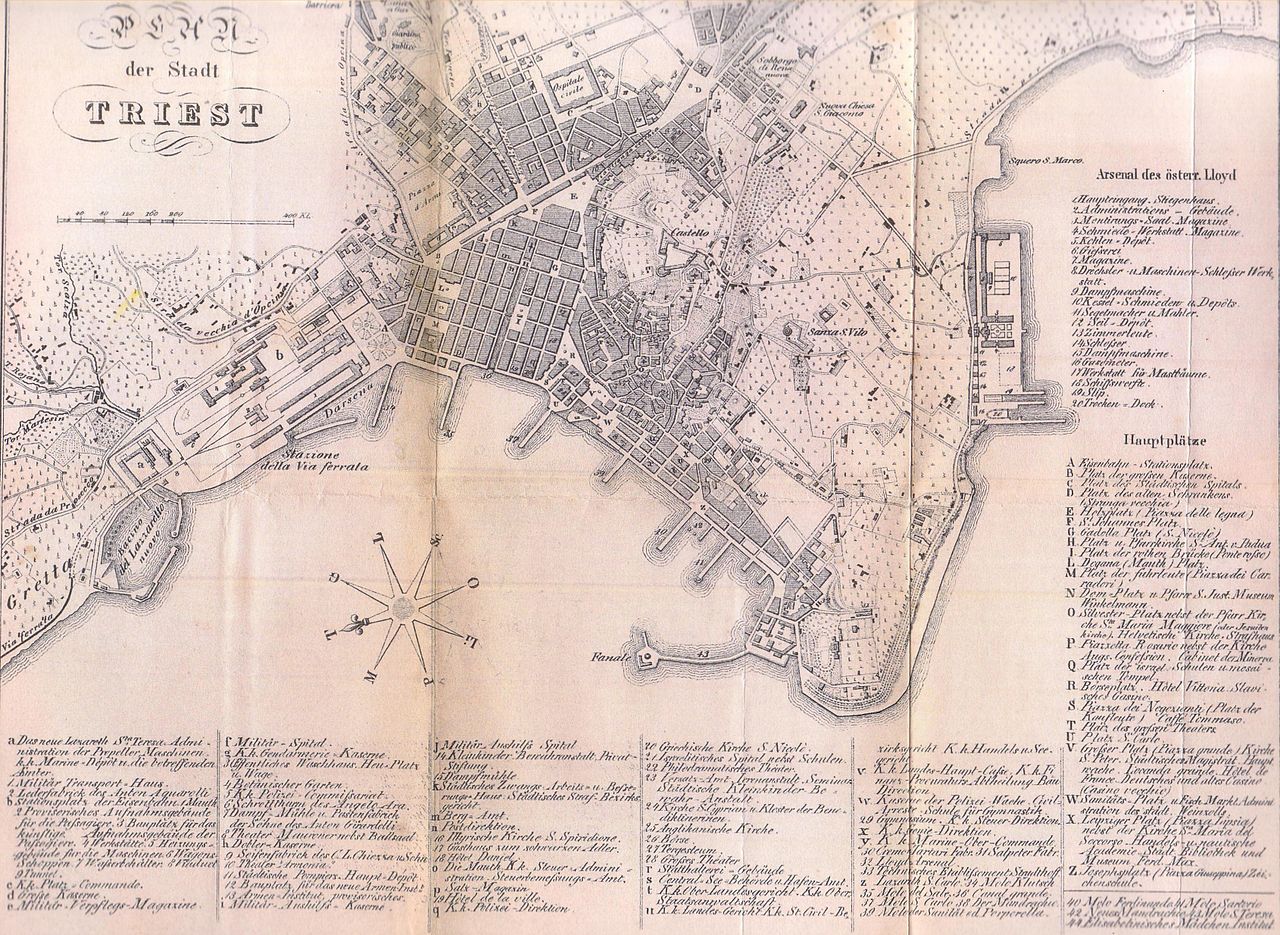

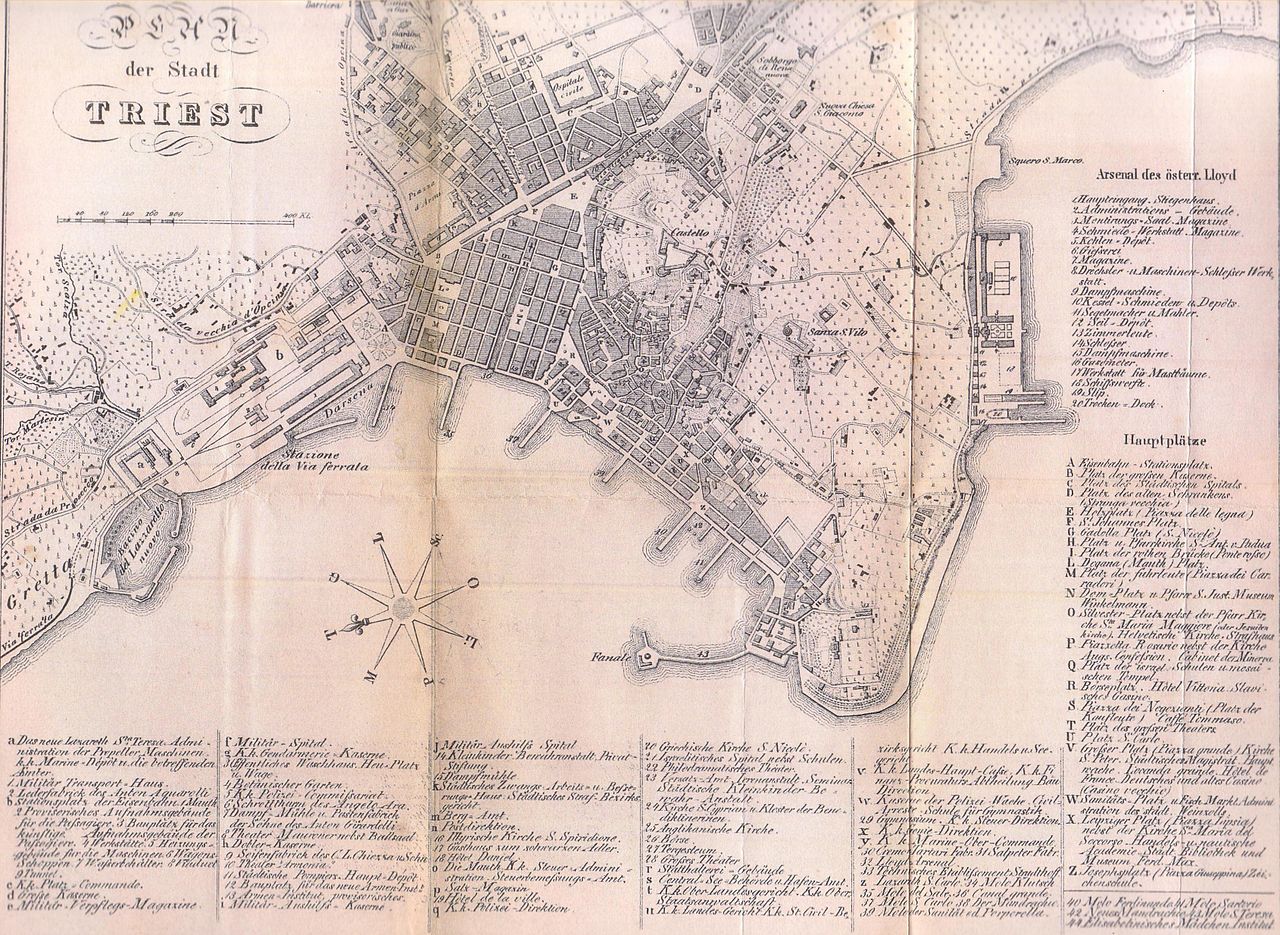

Trieste in 1857, 138 years after the proclamation of the free port, at the time of the arrival of the railway

Trieste was occupied three times by Napoleon's troops, in 1797, 1805 and 1809; in these short periods the city definitively lost its ancient autonomy with the consequent suspension of the status of free port. The first French occupation was very short, as it began in March 1797 and ended after only two months, in May. Frightened by the imminent arrival of Napoleonic troops, part of the population had left the city; whoever remained was ready to rise up against the French soldiers. The Napoleonic government, however, was not as revolutionary as the fugitives expected, who decided to return to the city a few days later. Napoleon visited Trieste on 29 April. In May, French troops left the city under the Leoben Agreement. The second French occupation began in December 1805 and ended in March 1806. Despite the brevity of the first two occupations, the democratic ideas brought by the Napoleonic troops also began to spread to Trieste, where the Italian identity began to mature. The third occupation began on May 17, 1809. Starting from October 15, Trieste was incorporated into the Illyrian Provinces, which also included Carinthia, Carniola, Gorizia, Veneto Istria, Habsburg Istria, part of Croatia and Dalmatia. . The occupation ended on November 8, 1813, following the Battle of Leipzig.

Returning to the Habsburgs in 1813 Trieste continued to develop, also thanks to the opening of the railway with Vienna in 1857. In the 1860s it was elevated to the rank of capital of the Land in the Austrian Littoral region (Oesterreichisches Küstenland). Subsequently the city became, in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the fourth urban reality of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (after Vienna, Budapest and Prague).

The commercial and industrial development of the city in the second half of the 19th century and in the first fifteen years of the following century (30,000 employees in the secondary sector in 1910) led to the birth and development of some pockets of social exclusion. Trieste at the time had a high infant mortality rate, higher than that of Italian cities and one of the highest rates of tuberculosis in Europe. The fracture between the countryside, populated above all by Slovenes, and the city, of Italian language and traditions, was also deepening.

Ethnic and linguistic groups in the Habsburg period

In the Middle Ages and until the beginning of the 19th century, Tergestino was spoken in Trieste, a dialect of the Rhaeto-Romance type. The only written language with an official character and a language of culture, was instead, during almost the entire medieval age, Latin, which was joined, on the threshold of the modern age (XIV and XV centuries), by Italian (spoken, as mother tongue, from a small minority of Trieste) and, subsequently (from the second half of the 18th century), also German, which however remained limited within a purely administrative sphere. In a report sent to the Empress Maria Theresa, Count Nikolaus Graf von Hamilton, who held the office of President of the Intendency of the city of Trieste from 1749 to 1768, described the use of languages spoken by the inhabitants of Trieste as follows:

“The inhabitants use three different languages: Italian, Tergestino and Slovenian. The particular language of Trieste, used by simple people, is not understood by Italians; many inhabitants in the city and everyone in the surrounding area speak Slovenian. "

After the establishment of the free port and the beginning of the great migratory flow which, which began in the eighteenth century, intensified further in the following century (with a clear predominance of Venetians, Dalmatians, Istrians, Friulians and Slovenes), the Tergestino gradually lost ground in favor both Italian and Venetian. If the former was established above all as a written and cultural language, the latter spread between the last decades of the eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century as a true lingua franca in Trieste. Among the linguistic minorities, the Slovenian one (present in the Trieste Karst since medieval times) acquired a considerable weight in the city in the second half of the nineteenth century, which on the eve of the First World War represented about the fourth part of the total population of the Municipality.

Thanks to its privileged status as the only commercial port of a certain importance in Austria, Trieste always continued to maintain close cultural and linguistic ties with Italy over the centuries. In fact, although the official language of the bureaucracy was German, Italian, already a language of culture since the late Middle Ages, imposed itself in the last period of Habsburg sovereignty, in all formal contexts, including business (both on the Stock Exchange and in the private transactions), education (in 1861 an Italian gymnasium was opened by the Municipality which joined the pre-existing Austro-German one), written communication (the vast majority of publications and newspapers were written in Italian), finding its own space even in the municipal council (the Trieste political class was mostly Italian-speaking). It was often spoken, along with Venetian and other languages, even in informal contexts. Pietro Kandler reports, in his History of Trieste, that:

"In Trieste the nobility speak German, the people speak Italian, the countryside speak Slovenian."